My name is Nathan Thomas Stretch. “Nathan” – as my mother recently reaffirmed – for the unpopular prophet of the Old Testament (on a related note – and for possible future expansion – I. Know. So. Many. Davids). “Thomas” for my opa whose Frisian name “Tinus” (say it out loud to yourself) was almost immediately anglicized upon his arrival in Canada from Holland shortly following the Second World War. My given names are such a lonely pairing from a Judeo-Christian point of view: the prophet and the doubter – together in otherness.

As for “Stretch”, well… this is a word you know and use frequently if you are a native English speaker. It is both a verb and a noun and is, you guessed it, of English origin. In Canada, the Stretch family were/are Anglophone residents of Quebec: stubbornly speaking English in the Eastern Townships about an hour outside of Montreal. I know almost nothing about the extended Stretch family. My grandfather returned from World War II with a “nervous condition” – as they referred to PTSD in those days – and died shortly after I was born. My grandmother – a proud “Harrison” with a well-documented genealogy of kith and kin – broke off contact with her in-laws shortly after her husband’s passing. My uncle David (David!) recently admitted to me that he frequently ran into his father’s brothers in town while growing up, but could never bring himself to refer to them as “Uncle”.

-They were

he said,

-the guys in the bar who were either in the band or in a fight.

I haven’t traditionally identified with the Stretch side of the family. I didn’t know that they harbored any musical talent until recently, when my brothers and I played at my grandmother’s funeral service. The locals, most of whom we had never met, were not surprised to hear us play together and blend in harmony. The Stretchs were well known musicians around town. My father’s lurking talent had not yet fully revealed itself to us – he had just recently taken up the study of the saxophone (his first instrument, if you excuse a dalliance with the recorder in the late sixties) at the age of 50. Neal Stretch was a renaissance man, a serious person, and a scientist. His was largely a history in absentia, according to me. I couldn’t have identified with him if I tried.

My mother Akke Smit was born in Holland and arrived in Canada when she was only a few months old. The Smits settled in Chatham Ontario and bred. Akke is the oldest girl (there is an an older brother, Hendrick – my uncle “Hank”) in a family of six siblings. My mother and her sisters are very close (in age, temperament, politics, etc.) and they all had children when they were in their mid-twenties. These have long been my people: the male children of my mother’s sisters. We are very close (in age, temperament, politics etc.) and used to roll around like a gang of wiry confidence men imposing a spiky, imaginative worldview on any-and-all who entered our zone of influence. Many of my cousins are committed artists and musicians, some are philosophers and preachers. We experience various degrees of precarity, most living liminaly. None of us are deeply established in the world of economics, but have instead staked creative or social claims outside of established institutions.

When I was three (or maybe four) my family moved to Englehart, Ontario: a town of 1800 people just north of New Liskard. My dad would practice medicine in an underserved area. We lived 15 minutes outside of town on the other side of a provincial park. The roads there were all blasted out of the Canadian Shield; you could feel them heaving in the deep frost – the dulled memory of a massive trauma to the land: its very granite bones.

My parents bought the abandoned shell of a massive log house and built it up around us as we dozed in dusty light-streams, curled up by stacks of timber. And even as my dad’s beard grew bushier, his eyes blacker, and his form gaunt, my brother and I thrived. And even though my mother’s loneliness yawned wide into a deep depression over time, I was enraptured:

By the land,

by the air,

by the trees.

I was alive in the world, the road rose up to meet me, and I fulfilled my agenda in absolution daily.

The log house in Englehart is my home. I hope my spirit will carve its way there again someday. My father is also strongly tied to it – albeit in a slightly different way. It is my assertion that he subconsciously imbued the house with his presence and meaning while building it, and may have accidently constructed a mausoleum for his person way-out in the frigid wilderness of Northern Ontario. He sacrificed while I thrived – maybe that’s why the house is such a potent totem for both of us. I know this is an overly messianic reading (doctors do often have god complexes mind you… although it all breaks down when you consider that it is his brother who is named David) and I know that my mother sacrificed too (there is a whole essay to be inserted about how my father traditionally constructs while my mother actively deconstructs) but I think there is some truth here.

Let me try to explain by telling this story:

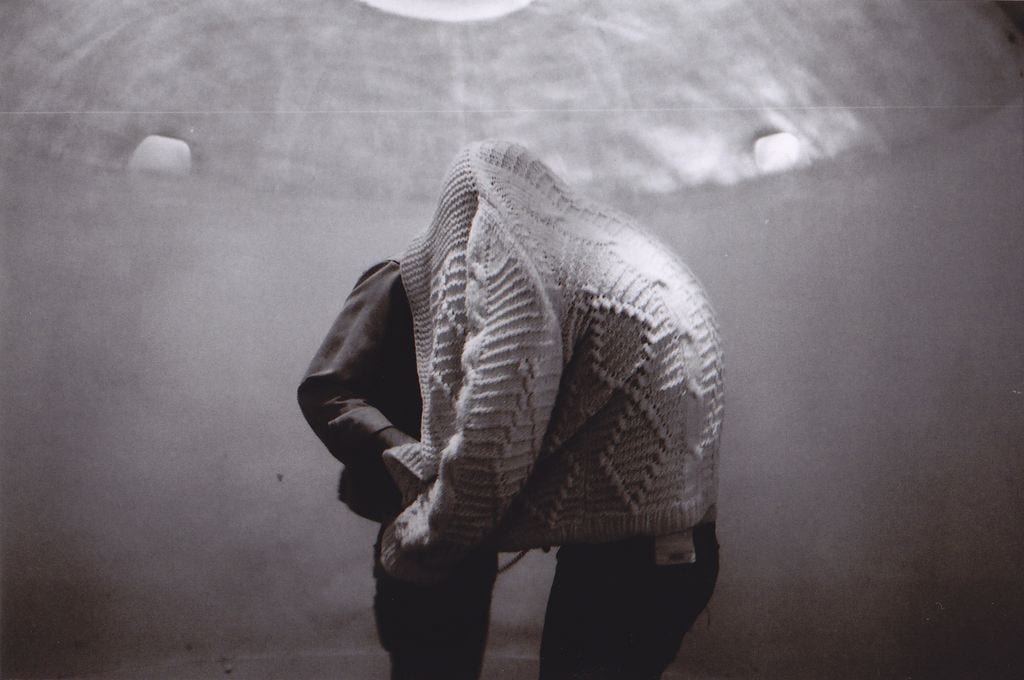

This is a song called “Funeral Shed”. Before my opa’s burial, I was milling about in the yard outside my oma and opa’s house with my teenage cousins. Our parents and my oma were taking up inordinate amounts of physical and emotional space, and we were uncomfortable in our ill-fitting dress clothes. A group of seven of us eventually congregated in the old tin shed our opa kept his gardening tools in. We were packed in there tightly, but felt only relief. One of my cousins took a picture while were inside. It is a black & white image – neatly composed – showing six sun-haloed silhouettes, the black handle of my opa’s lawn mower, and – outside the doors of the shed – the light-blasted figure of my father in his suit jacket. This picture, and the memory of that day, had a profound effect on me and I composed the song Funeral Shed in an effort to capture the particulars, the complex emotion, and the ideas born of the memory and facsimile of the experience.

The original lyrics (below) include an alternate chorus (ending) that describes my father’s funeral shed: the log house in Englehart. I think the song is stronger without the alternate ending, but I like the invocation of it all the same.

Funeral Shed

By Nathan Stretch

Seven cousins all in a funeral shed.

Black and white, alive or dead.

But are we happy or are we sad?

Seven boys in a funeral shed.

It was his: smells like dry grass and gasoline

Want to burn this thing down

But where would his spirit be

if we didn’t have that old, tin, backyard mausoleum?

Who’s that ghost outside the door?

face bleached white as bones: he’s overexposed.

I can just make out my father’s high lapels

Less a ghost, more of a kindred soul.

It was his: smells like dry grass and gasoline

Want to burn this thing down

But where would his spirit be

If we didn’t have that old, tin, backyard mausoleum?

All my brothers in the funeral shed, I must confess

I watched my father build his final resting place

It was Englehart, and I was only six

Have you seen your fathers build theirs?

It was his: smells like wood smoke and vinyl records

There’s a frost pattern on the window

Thank God it’s big enough

That I can go there too

when I finally give up the body

I will float through stone and ice

To that old wooden house in the country:

Paradise.

My opa was a soft, funny man. My oma was severe. They came to Canada to stake a claim. They were liminal: precarious. Their dislocation was profound, but in the end, their claim was successful. And inside their shared claim were sub-claims. My oma, in her hardness, claimed the house. My opa, the shed.

My father’s family has been in Canada for generations, living principled lives as Anglophones exercising minority rights to self-determine and converse in English whilst in French-speaking Quebec. You might also read this as a kind of futile, generational and active dislocation – which is how my father interpreted it. He spoke French and English indiscriminately and left town as soon as he was able. He too had to stake a claim.

Beautifully and profoundly written, Nathan. I have tears in my eyes.

As I read your post I found myself almost in the story. I think it was a combination of your gift of writing and storytelling, and my own strong love and connection to the northern Ontario landscape. My roots are on Manitoulin Island and there is a sense of peace and “home” that comes over me every time I am on the island. Do you have a recording of your song? I would love to listen to how you captured the text in song. Thanks for sharing.

The link to the recording is embedded in the text, but it’s not obvious :$ (thank you edublogs).

Here it is again: https://basslions.bandcamp.com/track/funeral-shed-2